Chapter 46: What about being a child do you miss the most?

Originally written November 2, 2021

I’m not one to indulge much in pining for the good old days. Actually I get much more nostalgic for the childhood days of my son and daughter than I do my own childhood.

In these pages I’ve already railed against “smug Boomer nostalgia” and people my age who insist that nearly all music released since Derek & The Dominos has been crap.

I certainly do miss some the fads, follies and fun cultural aspects of growing up in the 1950s and ‘60s — pro-wrestling at Stockyards Coliseum on Friday nights, triple-feature monster movies at the Mayflower Theater every Saturday, getting an airplane glue buzz from Big Daddy Roth and monster models.

I do miss certain long-gone restaurants etc. — and wholesome childhood activities like dirt-clod fights, exploring “the creek” near our house in Oklahoma and making prank calls. (The rise of caller ID ruined that last one for good.)

But all those are trivial compared with part of my childhood I truly miss, the people, family members, who no longer are here.

I’ve already written here of my Mom and my grandparents, Nana and Papa, my maternal grandparents. We moved in with them in their house in Oklahoma City in 1960s, after Mom’s second divorce. Indeed these are the people from my childhood I miss the most.

Papa died in 1967 at the age of 63. Nana left in 1986 not long after she turned 80. Mom died in 2013. She was 83.

My father was not part of my childhood at all. As I wrote in a previous chapter, I didn’t see him between the time he left home (I think I was only two) and when my Aunt Peggy, his sister-in-law, arranged for us to have dinner in the early ’80s, when I was almost 30.

And I never met my grandparents from that side of the family. I think (but I don’t really know) my father’s father was already dead by the time I was born. My grandmother on the Terrell side I believe outlived her husband by several years, but she definitely was gone by the time I moved to Santa Fe in 1968.

One extremely important person from my childhood who I miss was a lady named Gertrude Bowles.

She worked for our family as a “maid” but I loved her like a second mother.

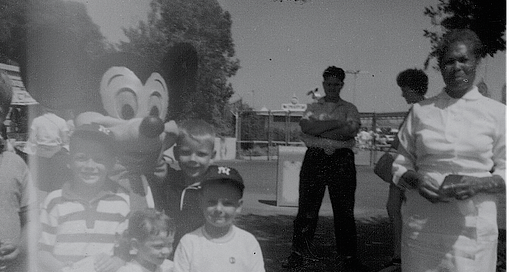

Gertrude didn’t live in our house but she was there every weekday. She went on vacations with us, including who knows how many trips to Santa Fe, a couple of trips to San Diego and once to Yellowstone Park.

Gertrude was African-American and also said she had Indian blood, which was believable with her facial features.

She suffered from some kind of skin condition which caused large patches of her skin to be whiter than mine. That disease is called vitiligo. Michael Jackson, when asked why his skin was getting lighter and lighter, claimed to have it. But, judging from photographs, his skin tone was far more consistent than Gertrude’s.

I believe my love for Black gospel music came from listening to Gertrude sing while she worked. I heard Gertrude singing her spirituals long before I became aware of Mahalia Jackson or Sister Rosetta Tharpe or Shirley Caesar. Sometimes, when she knew we were listening, she’d start clapping her hands along with her singing.

I don’t remember any specific song she sang except one minor-key tune that had a refrain in every verse that went, “… and I’m gonna tell ‘em when I get home …” That’s all In remember, except at least a couple of references to “The Lord” in some of the verses. (And I’ve never totally been sure whether it was “tell THEM” or “tell HIM.”)

I had no idea exactly who or what she was going to tell when she got home, but it sounded deep and mysterious. I have no idea what this song was, but I keep fantasizing that one day I’ll come across it, maybe while listening to the WWOZ gospel show some Sunday morning.

Unlike my Mom and my grandparents, Gertrude was a fairly strict disciplinarian. When my brother and I would start getting out of hand, she’d threaten to use a “switch” made of a tree branch on our “boom-de-ay”s.

That use of the word “boom-de-ay” adds a different level of understanding for the old song, as Joan Collins shows below:

It’s funny though. I clearly remember the threats — and taking those very seriously as a kid. However, I don’t have an actually memories of getting such a spanking from her. Maybe just the threat did the trick.

And from Gertrude I learned an important lesson about racism.

One night, I believe I was in second grade, Papa was driving Gertrude home and I rode along. As she got out of the car, I innocently said, “Goodbye, nigger!”

The first reaction I got was from Papa, who seemed horrified.

“You shouldn’t call her that!” he said, even though he was probably the first person I ever heard say it. In fact he always referred to the part of Oklahoma City where Gertrude lived as “Niggertown.” I just assumed that was what the residents there called it too.

And I assumed “nigger” was just what people including Black people called Black People. After all, at least at that point in my life, I rarely, if ever Papa or Nana use it in anger. They used it matter-of-factly.

But Papa’s reaction was nothing compared to Gertrude’s the net morning when she came to work.

She immediately tore into me, telling me in no uncertain terms I was not ever again going to call anyone that. It was hateful and hurtful and nobody deserved to be called that. She was the angriest I’d ever seen her.

And I cried. But it wasn’t because of my fear of “the switch.” It was because I’d hurt Gertrude and that was something I never wanted to do.

And as the years went by, I always thought of Gertrude when I heard this song by Sly …

No, I’m not claiming I never used the word again.

In fact, in 6th grade I got in trouble because a girl named Jane told our teacher that I’d been saying that. It was an all-white school at the time, but such racist chatter among us kids was pretty rampant. I’m still not sure why I was singled out.

Though I didn’t feel this way back then, now I realize that it’s actually commendable that the teacher, especially an elderly teacher in Oklahoma in the 1960s, reacted that way.

But, thanks to Gertrude, I never actually called anyone that again.

Our family left Oklahoma in 1968 and moved to Santa Fe. Gertrude and I exchanged a few letters, but I never saw her again.

Sometime before I graduated from high school she died.

I wish I could have talked to her as an adult.

I’d love to get her perspective on racism.

I’d love to find out what her life was like before I came around.

And I’d love to find out the name of that wonderful gospel song she sang.

And since I still don’t know, we’ll just have to settle for this Mahalia Jackson to end this chapter. I’m sure Gertrude would have approved:

I asked ChatGPT about a gospel song that contained the phrase "tell them when I get home," and it gave me this:

"Tell Them When I Get Home"

Verse 1:

"Tell them when I get home,

I'm gonna see my Savior's face.

Tell them when I get home,

I'm gonna sing of His amazing grace.

Chorus:

Tell them when I get home,

Tell them when I get home,

I'll be home, I'll be home,

Tell them when I get home.

Verse 2:

I've been tried in the fire,

But I made it through the storm.

Now my soul is weary,

But I'll be resting in His arms.

Chorus:

Tell them when I get home,

Tell them when I get home,

I'll be home, I'll be home,

Tell them when I get home."

There's bound to be a YouTube of that somewhere.

My mother drilled into me that I was never to use the pejorative "nigger" under any circumstances, long before I ever had the opportunity to call anybody that. We had a white neighborhood, white school, white church. Even our housekeeper Mrs. Woods was an old white lady. But I do remember being uncomfortable when my buddy Robert from across the street used the word a lot, and casually. I later learned that his grandfather, from somewhere in East Texas, was a leader in the Knights of the White Camelia, a notorious Klan variant.

Your grandfather George Roy Terrell died in 1965, and is buried in Sandia Memorial Gardens in Albuquerque, according to the find-a-grave website. A few years after his death, our grandmother Isabella (Belle) remarried to a man named Everett Stone, whom I think was a distant cousin of hers, and moved to Tucson, Arizona. She died in 1976, when I was in college. I remember that a few years earlier, my dad had flown out to Tucson to basically confront Everett and compel him to put Belle into a nursing home, because he couldn't take care of her after her stroke.