I’ve never been that much of a theater guy, though it’s probably safe to say that I’m a born ham.

I’ve never seen a play on Broadway, and I can’t remember the last play I saw that didn’t involve one of my kids. (Both Anton and Molly loved acting when they were in high schools as did my niece Lauren. And I saw almost all of the plays they were in.)

At the risk of being tacky (DEATH BEFORE TACKINESS!!!), I’d have to say my favorite play was one that I was in back in the early 1980s, You Can’t Take it With You, a three-act comedy by George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart, which premiered on Broadway in 1936, winning the Pulitzer Prize for Drama the next year. (Kaufman had written scripts for Marx Brothers movies.)

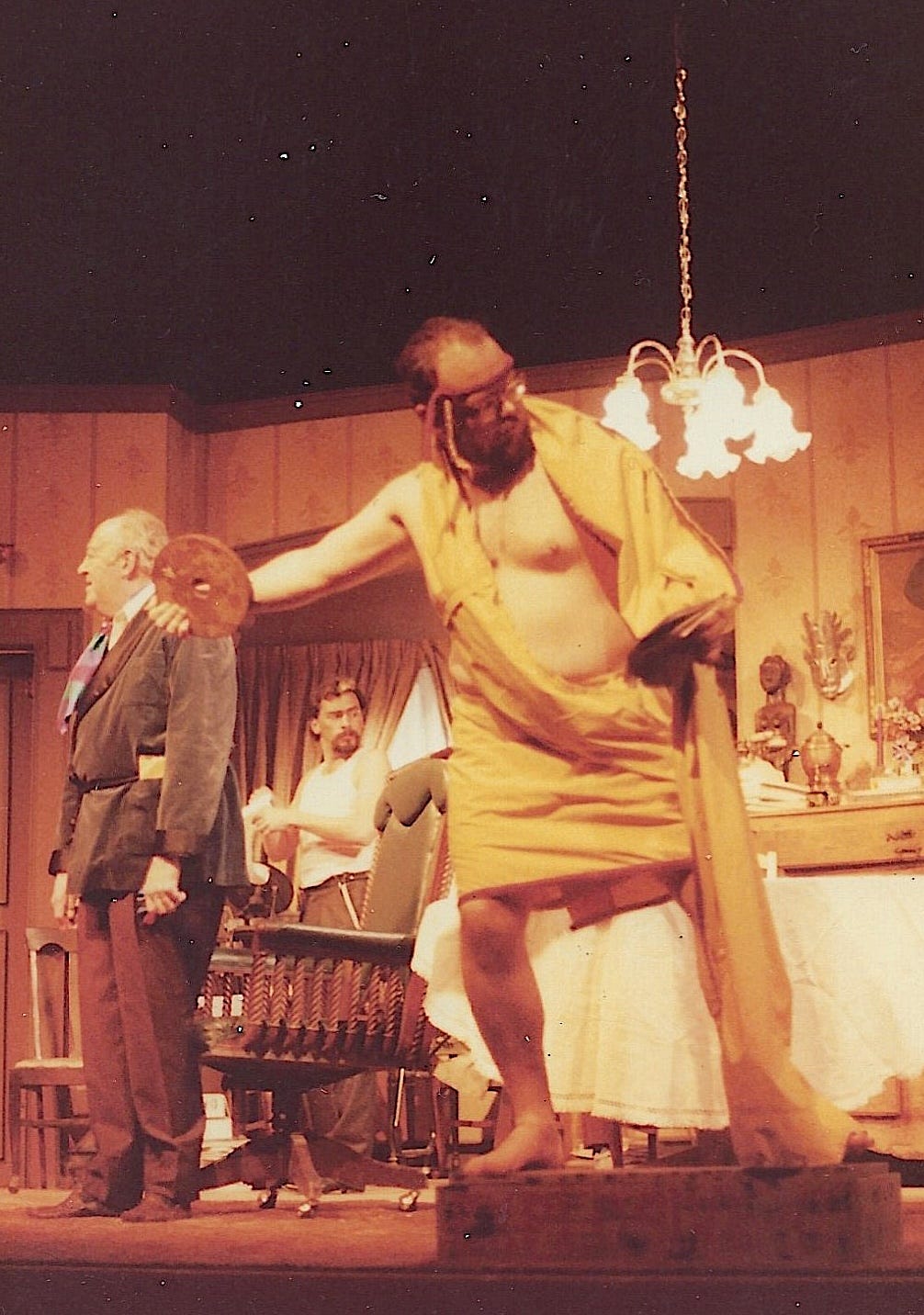

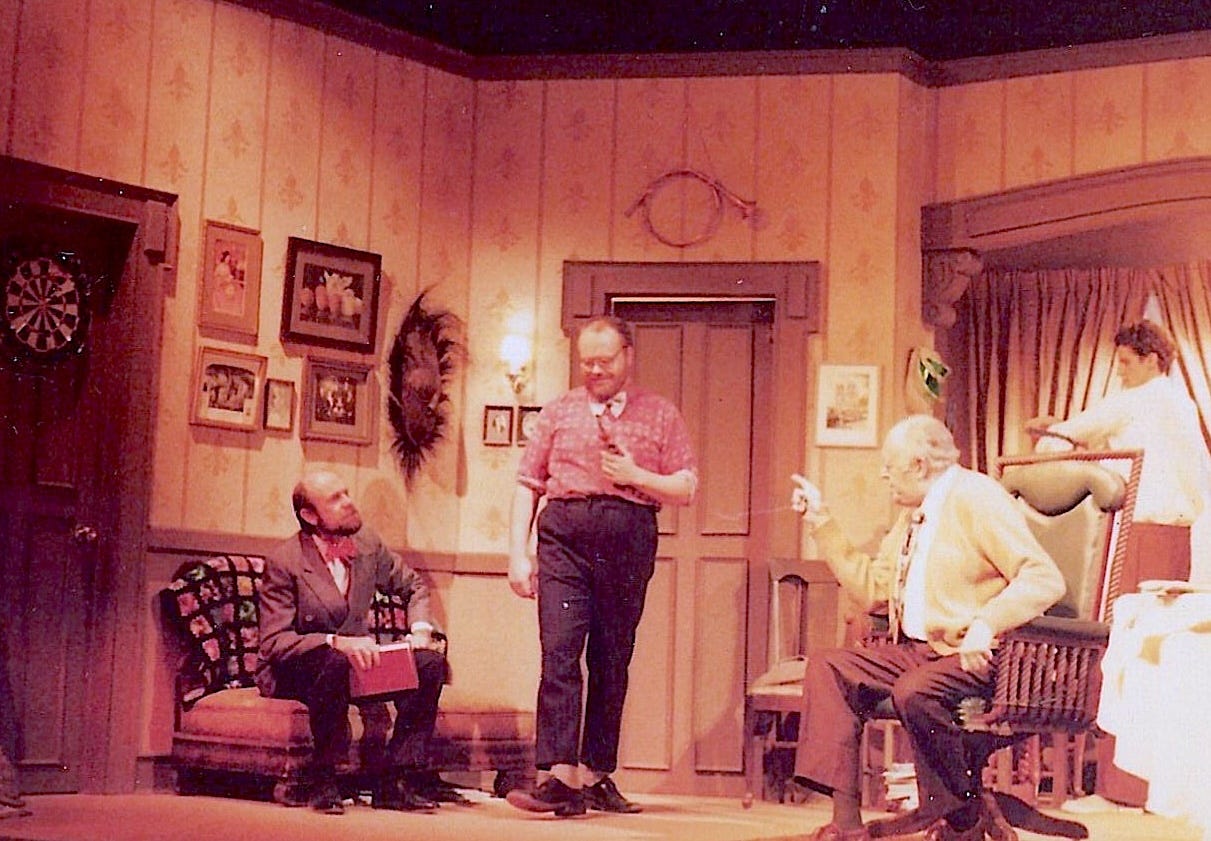

I was in the 1984 production at the Santa Fe Community Theater (now called Santa Fe Playhouse).

Mine was just a bit part. I played Mr. De Pinna, a one-time iceman who cameth to deliver ice to the eccentric but lovable Vanderhof/Sycamore household one day and liked them so much, he just stayed. (He was portrayed by British actor Halliwell Hobbes in Frank Capra’s movie.)

While the part was indeed a minor one, De Pinna does have a few hilarious moments in the play. My appearance onstage in a toga — to model for a painting by Penny Sycamore, one of the major characters — always brought the house down.

I wasn’t as much of a theater kid as my own children. My drama period actually was in junior high, in which my career highlight was playing the villain in a melodrama that our speech class performed for the entire school (Eisenhower Junior High.)

After moving to Santa Fe in 1968, I did a few plays in Mr. Suazo’s speech class (Our Town and Shirley Jackson’s wickedly horrifying The Lottery among them.) After that, though, the acting bug left me, at least until 1984. I was working full time at The Santa Fe Reporter then when my friend, and then-wife of of our arts editor, Bob Graybill, Nadine Stafford asked me to play De Pinna in the play she was directing.

Soon after that, Graybill asked me to be in a play he was doing with the newly established Santa Fe Desert Chorale. It was a strange adaptation of Danse Macabre (“Dance of Death”) for actors and chorus.

I played a drunken sailor who had died and was facing “Death,” an archetypal Grim Reaper spook who apparently was responsible for making the decision to send you to either Heaven or Hell. Like all the characters except Death, I had just one scene.

And all of our lines rhymed. The sailor’s best couplet was “… But my old Adam, rude and proud / has cast my goodness in a shroud. …” (What’s an “old Adam? Use your imagination!)

The Desert Choral did an excellent job with the music. But this should have been my walk-on song:

Working for a weekly newspaper it wasn’t hard to get nights off for rehearsals, so for a brief period it looked like drama was going to become my cool new hobby.

However, in late summer of 1984, I got a job with the Albuquerque Journal North covering Santa Fe city government. This involved many night meetings, which meant my brief time as a local character actor was over.

It was fun while it lasted.

There are a few memories of You Can’t Take it With You that always have stuck with me.

First was working with Billy Griego, who played Boris Kolenkhov, the ballet teacher for one of the Sycamore daughters. (“Confidentially, she stinks!” Kolenkhov says, describing Essie’s dancing skills to her grandfather.)

Like my part, Billy’s role was relatively minor, but he usually got more and heartier laughs than anyone.

Just a few years after this play Billy, who I believe was younger than me, died of AIDS, the first person I knew who was a victim of that disease. I knew his older brother, Phil Griego, who at the time was on the Santa Fe City Council. Phil later was elected to the state Senate — and later went to prison on corruption charges.

But to his everlasting credit, Phil became a champion of the AIDS community. In 2005, Phil sponsored and convinced fellow legislators to pass the Billy Griego HIV and AIDS Act, which requires the state Health Department to provide education, prevention, and treatment services to HIV-positive people in the state.

But the main thing I remember was the performance of the play in which my sister took Molly, then 3, to see me on stage.

I was thrilled for Molly to be there, but I’d not realized that there was one scene that would upset her. It’s when the FBI raids the Vanderhof/Sycamore home. At the time of the raid, De Pinna is supposed to be downstairs in the basement making fireworks — the major obsession of Penny Sycamore’s husband Paul.

De Pinna basically was pushed onto the stage by tough-guy FBI agents, who manhandle him. Out in the audience little Molly was terrified seeing these goons rough up her dad.

In this part of the scene De Pinna is panicking because he’d left his pipe burning down in the basement. (At the time, in real li9fe I smoked a pipe, which was a prop in the play.)

Shouting about his pipe, De Pinna breaks away from the federal and goes running down to the basement and the next thing the audience sees is the curtain closing as a bunch of fireworks explode. (This was done backstage where our stage manager Bruce set off several strings of firecrackers in a metal trash can.)

In the subsequent act, the first time De Pinna appears again onstage, his head is bandaged. Onstage, I heard my traumatized daughter, out in the audience, gasping.

A few weeks later, I was with Molly at a grocery store when I spotted Donald, who had played one of the FBI agents who’d abused poor Mr. De Pinna. We greeted each other as friends and I introduced Donald to Molly, explaining that he was the actor who’d pretended to knock me about.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen a kid look as apprehensive as Molly did in that moment.

But even without these personal memories from this play, I probably would still consider You Can’t Take it With You to be my favorite play, not only due to its zany humor but because of its underlying message.

Although the family and those who have attached themselves to it are played as sweet kooks, Kaufman and Hart are laughing with them, not at them.

The real objects of ridicule are the obnoxious FBI agents who are under the paranoid sway of an early Red Scare and the stuffy disapproving parents of his granddaughter’s boyfriend.

“Grandpa,” aka Martin Vanderhof, tolerates the Kirbys, but isn’t impressed by their money. Instead he pities how the couple don’t seem to get much pleasure out of life. In the final act he tells Mr. Kirby that he ought to enjoy his life and his riches while he can because “you can’t take it with you.”

Grandpa is a classic individualist who has an enviable outlook on life. Very little fazes the old coot. He delights in the eccentricities of others — De Pinna, Kolenkhov, the drunk actress who comes to visit, the Russian “Grand Duchess,” who, in exile, works as a waitress.

And Grandpa encourages the creative passions of his family — Essie’s dancing, Ed’s xylophone playing, his daughter Penny’s painting etc.

Even Grandpa’s weird hobby of going to commencement ceremonies where he doesn’t know any of the graduates seems like a positive trait, i.e. celebrating the achievements of young folks.

[Note from 2024: Just a few months ago I felt a little like Grandpa one day when out on an afternoon hike, I came upon a procession of trucks on Jaguar Drive. It was a Capitol High School graduation parade –an event I’d never been aware of. I got a real kick seeing these kids celebrating this major milestone in their lives and felt honored to witness it.]

So while this 1930s screwball comedy is dated, its message is timeless.

Pursue your crazy dreams.

Be kind and tolerant.

Enjoy your life.

You can’t take it with you.

xxxx

Bonus: Here’s an appropriate bluegrass song by Australian singer Paul Kelly: